Dual Intent

An incomplete and inconclusive personal immigration history, belonging to someone who is totally not me.

The slideshows that play on the screens in the waiting spaces of American visa centers are much like those illustrating the modules of an IELTS prep textbook. A useless reference: if you haven’t seen one, you likely haven’t seen the other. They are unmemorable images—stock photos of downtowns, national parks, and diverse people in t-shirts and flannels and backpacks, smiling at each other as they shake hands, or pass a book between themselves, or sit side-by-side, talking, one of them perhaps writing something down in a notebook, studious, hard-working. They don’t say much about life in America, except that you should be so lucky to experience it.

Once you’ve passed security, your bags scanned, metals detected, passport checked, and appointment verified, you’re told to put everything except the necessary documents in a small locker—your phone, your book, your bag. You pull a ticket with a number on it and are pointed to a room with rows and rows of chairs, where you and other visa hopefuls will sit with nothing to do besides watch the slide show, occasionally shifting your gaze to the screen where your ticket will come up, asking you to proceed to a numbered window. There, you will hand an officer the folder with your documents, they will check that you’ve printed all necessary forms, that the grid of four Visa portraits you provided is recent enough, and send you on your merry way, with another numbered ticket, which buys you 2-4 hours of anticipation for your Visa Interview, during which you will keep watching the slideshow.

If the visa center is small enough—which they tend to be in the world’s minor capitals—you might be able to hear the Visa Interviews before yours. You’ll learn about the degrees people hope to acquire, or the reasons their wife and daughter aren’t coming with them, what they plan to do while on their American sojourn, what they plan to do when they return from it, and if they definitely, swearing on the Bible and their mother, intend to do so. You can tell from the conversation when it’s going well or when the officer has already decided not to grant their interviewee the visa, and go through the rest of the questions out of mere obligation to procedure. You fear that this might happen to you and so you rehearse in your mind what you might say and how you might say it. You remind yourself that you need to respond strictly to the question asked, no conversational flourishes, spare on context until asked further. The full truth is usually more complicated than immigration law prefers.

The hours you’ve spent at American Visa centers likely amount to a few days of your life. A slew of B-1’s cycled through in “tourist” trips to see relatives who were lucky enough to anchor themselves in the United States. A J-1 that allows you a brief internship. Then, an F-1, as graduate school stretches to four years (Optional Practical Training included), followed by an employment-based visa finally not granted; you knew exactly what was happening when the officer’s line of questioning swerved into the probing. You were told that you did not have strong enough ties to your country of origin for it to be plausible that you had no plans of staying in the U.S.

After nearly a year of roaming Europe—during your time in graduate school, you watched authoritarianism continually tighten its grip on your country of origin and its assault on its neighbor immediately turn into a war that will stretch over years and alter history; you resolve not to go back—you finally learn that you have won a literal lottery, and were granted permission to apply for an H-1B, which not so much gives you permission to work in the United States, but rather your employer to hire you. Another half a year later, you get soaked in a torrential storm as you stand in line for the Visa Center; for hours you sit there, damp and anxious. There was a moment in the interview when you thought it—everything—was over. You are asked to step aside and take a seat while your documents are whisked into the back office; you keep watching the fucking slideshow. You are called again once the lines are no longer and the center has emptied, to be told that you were, after all, granted the visa. Relief.

America was always the goal. You could never quite explain why, but you rarely had to: there were plenty of kids with the same goal back home, whose disapproving relatives, like yours, dismissed the project as the product of Western brainwashing. Perhaps they weren’t entirely wrong, certainly, you were aware of the contradiction between your rosy view of things and what you, for a fact, knew. Your first memories of the TV were tied to American catastrophe: Columbine, 9/11, the Iraq War, because your father watched a lot of CNN, which, later, you would come to joke, was responsible for your knowledge of English. You cried on your couch in London, where you had moved because it was an easier-to-access English-speaking metropolitan center, when Donald Trump was first elected as if he were president of the country in which you lived.

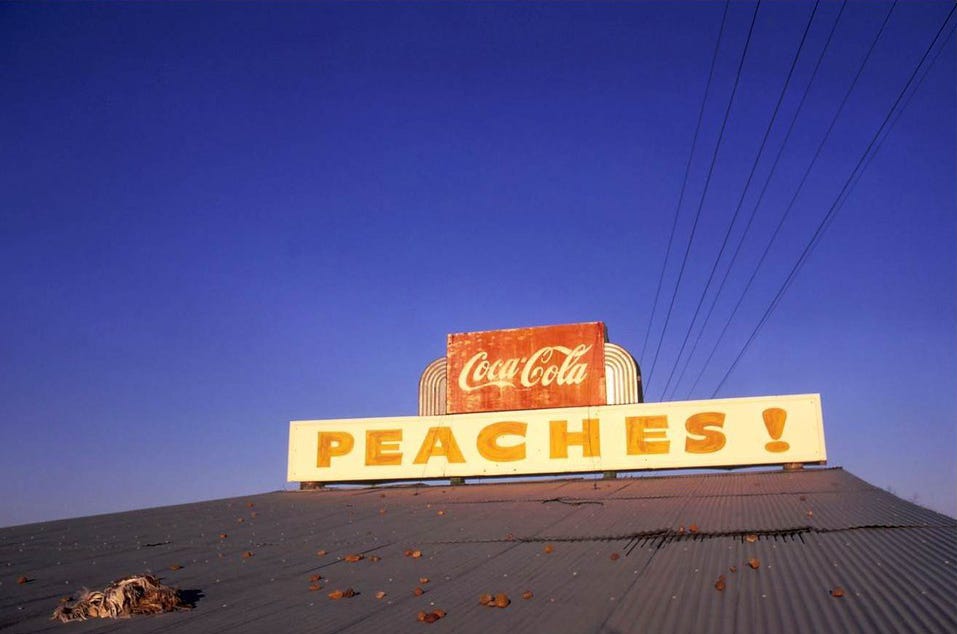

And yet, despite all of that, America continued a dual existence in your mind as the place that both housed (or exported, as it were) horrors and as a promised land of freedom. You could not articulate what freedom meant to you, but you guessed that it was liberty, and where else would that be found other than in America? They had the suburban malaise that you had so come to romanticize; they had Lana Del Rey there, Route 66, and Alex Honnold was free soloing El Cap, you could buy Glossier products, and there was key lime pie at the diners, and because you could easily surround yourself with people who did not disagree with you. You could participate in a life that looked inside just as it did on the surface.

By the time you have finally made it to the United States in a manner, as far as USCIS is concerned, still not permanent, but one that would allow you to settle in for a little, it is the Fall of 2019, and your willful naïvite has subsided a little. You were conversant, if not specifically interested, in the all-American subjects of the opioid epidemic, of climate inequality, of systemic racism, their histories, how they are all tied together. You were curious about how parallels could be drawn between American reality and that of your country of origin, both of which were, still, fairly abstract to you. You were coming to understand, more profoundly, that when you have the kind of privilege that allows you to simulate a transposed version of itself elsewhere, the impact that political forces are supposed to have on your life is largely theoretical. Still, even if you were arriving in Trump’s America, he would not be president for that much longer, and you were enchanted by New York being itself in ways that you couldn’t understand from afar, even if it turned out that nobody had a washing machine at home. The institutions here, you and everyone else kept repeating, they still function.

You could become a New Yorker, but you could not become an American, not so easy, not so fast. On the first day of orientation at grad school you were pointed towards the fine print that you had neglected to read before obtaining the Visa that got you here: you may have come here to learn to be a writer, but not a published one, because you can’t engage in any form of employment or professional development that is not strictly sanctioned, i.e. not confined to your university. That wouldn’t matter so much, because you still needed to learn so much, more than you had realized, like how to really read a text or that the writing you wanted to do was not the writing you should be doing. (It would matter later, when you needed to apply for the next Visa, and there was not enough public proof of your talents, such as to be granted Alien of Extraordinary Ability status.)

Then, six months into your new life in America, the pandemic. You hunkered down with the rest of New York, listening to the endless stream of sirens that had come to be the soundtrack of that first COVID spring. You would go for early morning runs, in a mask, from the East Village to Washington Square Park, and look at the trees that were still blooming, despite everything. A month or so in, you would make your way to Los Angeles, where your boyfriend at the time lived, and stay there for the next three. You would not go home that summer, and for at least another year; instead, you would lie in the yard and read Marie Antoinette’s biography as helicopters buzzed like dying flies abovehead, spending hours intimidating the mass protests; you would have had enough and joined the protests yourself, because here you were not afraid to express solidarity. Friends would get banged up and teargassed, but beyond the immediate brutality, this was not likely to signify years and years of police persecution as it did back home.

One morning, you woke up to an order for all international students to leave, if they were not to attend classes in person, which universities were still not planning on holding as the new fall semester drew close. For a few days, you thought that this was it, and spent them calculating what you might do if you had to go back home, if you’d still stay in graduate school, how many years it would be before you could get your next Visa. But then the Ivies sued the administration, and that was that: the institutions were functioning.

Still, you were now aware of your own precarity, that all the effort you’ve put into building a home could go up in smoke, should the institutions malfunction. You were now cognizant of the expiration date on your American Dream, and in those three years that you still had, you needed to Figure It Out. In the meantime, you would watch your brother get married via private Youtube livestream, because to Figure It Out, you decided that you had to stay put.

Pandemic living became its own pacifying routine, in which you had the time and space to build the New York life you wanted. You surrounded yourself with the friends you made in graduate school, having sensed kinship over Zoom, people committed to writing—to literature—in the same ways as you were. You felt that the lives you lived were the same, that the same kinds of futures were available to you in this place, if you were just able to get the question of immigration out of your way. You had never thought yourself capable of writing a book, but that is what the plan now was, because this is what you were told: you would write a book, and you would sell it, and get a talent Visa and the rest would be history. It would take up, more or less, the lifespan of your current Visa.

But history kept shifting, and you couldn’t orient yourself quickly enough; the book remained unwritten as you busied yourself with stretching your mind to accommodate the terrors of war, which somehow kept expanding, while even entertaining the thought of moving back home to Figure It Out became equal to giving up, if not to suicidal ideation. Starting over somewhere completely else would be possible—always is—but those who choose a life of immigration are especially susceptible to decision-making guided by sunk-cost fallacy, especially when they’re out to prove that all of the choices they’ve made were the right ones, in the end. Well-meaning friends would offer marriage to save you; they would get to be a hero (the American Dream for Americans), and you would be secure enough to plan a life here. But you declined each time: you knew what life consumed by immigration looked like, and you did not want to take half a decade from someone, as prepared as they were to give it to you. You wanted the real thing; if you were to complete your American immigration arc, you would want to do it yourself, no shortcuts, the real way. For USCIS to decide that the country can’t do without your talents. Or for someone to make an honest American woman out of you, or at least a Green Card holder, because they did not want to live without you, not because you would stop at nothing to become one.

And so, you have spent the better part of a decade in the status of a Non-Immigrant Alien, which means that when they pull you aside into the room for additional questioning and ask you where you live, you are to tell them that you live in the city of your birth, even if your trips home are sparse. The only progress you’ve made, immigration-wise, is that you are now on a dual intent Visa and no longer have to hide what is in your heart from border agents, namely making a permanent home here, in America. You have become fluent enough in the rules and regulations of your existence in the United States and the spectrum of alternatives, available or not, such that you might pass yourself off as an amateur immigration lawyer. You find yourself continuously coming out as not American and have learned to accept graciously as a compliment each time that you are told that your English is “flawless,” even if, at times, it makes you feel like a talking dog. You switch to an accent, transposing the mouth posture you use when speaking your mother tongue into English as a joke, and everyone is delighted.

Because you live in America, you know that you are a white woman before anything else, undetectable as foreign, and that you are afforded the corresponding superficial advantages. You don’t have to worry about being stopped and having your documents checked, which you don’t carry with you out of fear of losing your passport. If something like that does happen, you aren’t likely to be questioned beyond confirming your status. When you learn that your friends from home, fellow “emigrés” who are, granted, more recent arrivals with detectable accents, carry a folder of forms confirming the legality of their presence in the US, you wonder if you are being complacent.

An employed, tax-paying person, invested in the political life of the city and country in which you live, you are reminded of the truncated rights with which you exist here daily. You keep a low profile and try to express any feelings you have about the goings-on in America only obliquely—you know that the next time you stand before a Visa officer, they will have seen your social media profiles. And if they’re sending away Australians for merely reporting on the obvious, brutal overreaches in government response to campus protests, then you certainly are at risk. Or are you just being paranoid? In any case, you can’t feel aggrieved about any of it: you chose this. It’s a choice you question every day, as you watch the walls narrowing in on you — when you arrived a year ago, you assumed that you had six years here, but one October morning you wake up to an abrupt change in H-1B policy, wherein renewing your visa will now cost your employer $100,000 and you know they aren’t going to pay that. So two more years is what you have.

The walls, of course, are closing in not just on you: you hear the same conversations begin here, among Americans, as the ones you’ve been having with fellow Russians over the last decade. It feels an awful lot like home, and that isn’t a good thing. You draw parallels, as you observe creative applications of the law in service of strongman politics; you think a lot about how during the 2021 protests in support of Navalny in Russia, most protesters were detained, nominally, for “violations of sanitary regulations” because they were gathering during a pandemic. How every Friday, a new slate of “foreign agents” is announced, ridding those inconvenient to the regime of any financial or political agency, so as to cast them out, if not to imprison them. You see the brute force of ICE turning in on American citizens standing in the way of their quota-enforcement. If they’re killing white people on camera, how many murders happen within the walls of what amounts to concentration camps? You know by now that when the government treats people it considers its own like immigrants, things are much worse than you could have suspected, but that only speaks to the limitations of your own imagination and perception; none of this is new.